Antiracism in Healthcare |

|

Dennis H. Novack, MD. Associate Dean of Medical Education at Drexel University College of Medicine Camille Burnett, PhD, MPA, APHN-BC, BScN, RN, DSW, FAAN, CGNC Vice President | Health Equity | US Equity Portfolio, Institute for Healthcare Improvement

|

|

© by Drexel University College of Medicine

|

Dennis H. Novack, MD

When you have completed this module and associated workshops, you will be able to:

-

explain how structural, cultural, and individual racism have shaped our common history and have led to vast societal disparities in education, policing, wealth and healthcare;

-

commit to being antiracist in your attitudes and behaviors;

-

contribute to creating an antiracist learning culture for healthcare trainees that honors diversity, equity and inclusion: where all trainees are respected, where faculty model respect and empathy for all patients, colleagues and staff, and where trainees feel empowered to contribute to a culture of mutual learning;

-

provide examples of how your increased self-awareness and reflection have helped you recognize your individual and cultural biases and how you use this awareness to seek to understand and empathize with your patients and clients of color, and to deliver equitable care to all;

-

have the moral courage to act as an ally and upstander for your minoritized colleagues and patients;

- use your understanding of structural, cultural and individual biases to advocate for positive changes in your institutions and communities that will lead to equitable care for all.

We hope this module will guide you in thinking about and executing ways

to engage holistically with your patients/clients as full, authentic beings.

By examining historical, social, economic and political forces that shape medicine

and human health, we offer ways in which to reconceptualize healthcare through

a social justice framework.

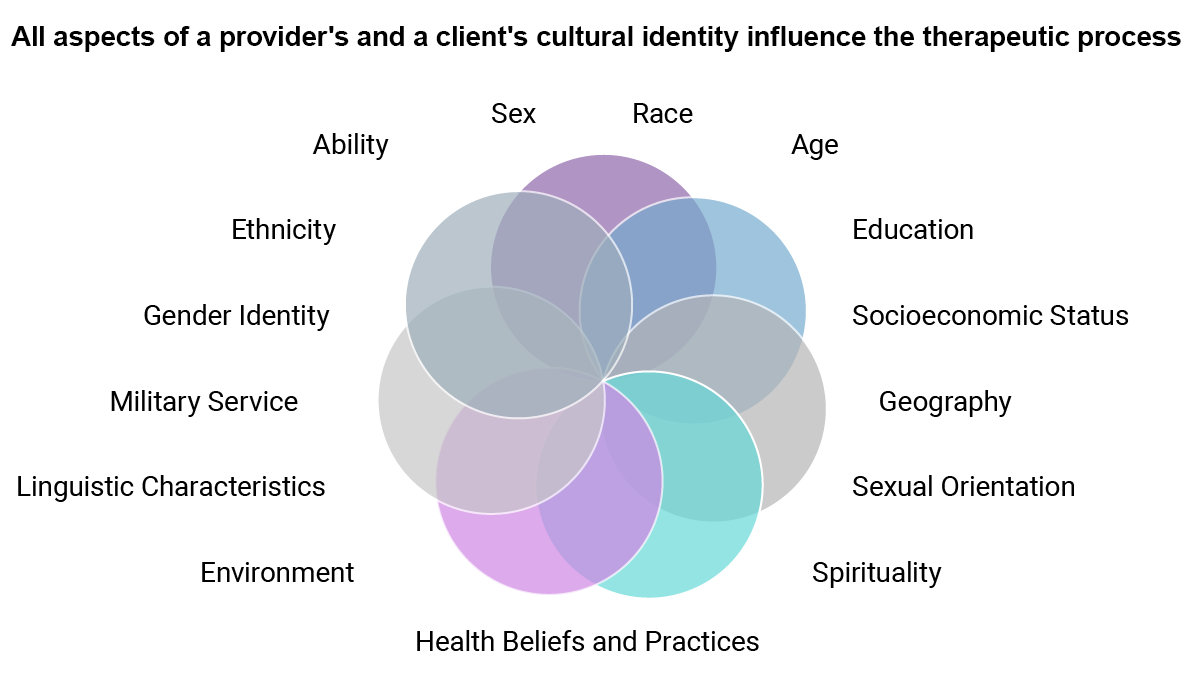

The first premise of this framework is that health practice must be truly patient-centered;

and that happens when the whole patient is seen. All patients' intersectional identities

shape their experiences and particularly inform their experiences with health and healthcare.

Two foundational principles of

do no harm

and

diversity drives excellence

have helped shape and inform the orientation of this module.

Too often in Western medicine, we separate the person from the disease, and when we do this,

we do harm. The intent of seeing disease, rather than the person, could be seen as promoting

equity in care. However, this perspective only reinforced existing structures of

bias and ultimately created greater healthcare disparities. The structures of dominance

within a society are mirrored in that society's healthcare system.

When a society is at its best, the disparities in healthcare may be minimized, but remain.

When a society is not at its best, the disparities in healthcare are exponentially worse.

The cost and damage are exponentially worse (National Center for Health Statistics, 2015).

Fortunately, all social systems are created and run by members of society and thus can

be changed and improved. As participants in the U.S. healthcare system, we are

both responsible for and capable of bettering this system. Establishing a social justice

framework for healthcare provides specific approaches to decreasing disparities and dismantling

structural inequities, such as racism. Racism is a public health issue and a root cause of

many inequities faced by minoritized populations, greatly affecting their health outcomes.

Therefore, learning about and understanding how to be anti-racist is a necessary competency

for all health providers.

Research shows that diverse groups are smarter, more innovative and reap greater financial rewards.

(Phillips, 2014). While the evidence is clear, the impact of inclusive and diverse practices

has far-reaching implications for the future of healthcare practice, our communities and for

the patients we serve. Leveraging diversity enhances the work we do, how we do it and with whom

we do it. Diversity facilitates new knowledge, ways of seeing and empowerment that are of

benefit to us all. We experience ourselves and each other in a more deeply connected way,

which allows all of us to practice to the fullest extent of our competencies.

For all these reasons, we welcome you to this module, so you can learn to cultivate diversity

in your teams, in your patient care and in your personal life. We believe that in doing so,

you will achieve excellence and more satisfying careers in healthcare!

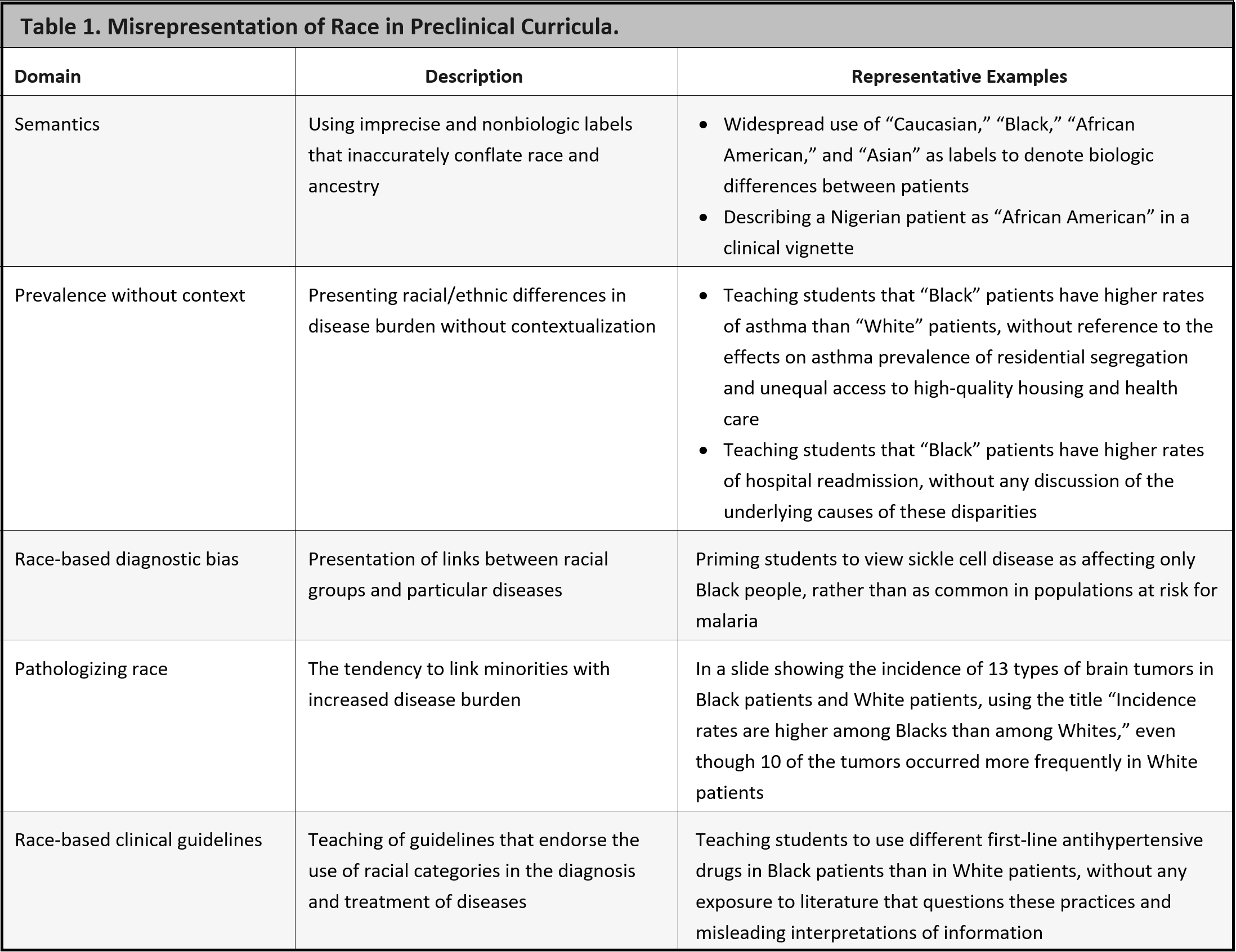

Though it is now widely recognized that race is a social construct, biases and stereotyping based on outdated notions of biological differences persist in medical practice. Throughout American history prominent physicians have conducted (pseudo) scientific studies and contributed writings to "racial science" that have supported notions of inferiority of people of color. Physicians and physician organizations such as the AMA have been openly racist in the past. Times are changing, though, and today’s healthcare students and providers can lead the way in providing just and equitable care to all.

Would you consider yourself racist?

Perhaps the great majority of healthcare providers would deny that they are racist or let

biases influence their patient care. Yet there are great disparities in healthcare and health

outcomes between racial groups. Certainly, structural racism accounts for many of these disparities,

i.e., policies that have affected access to care, insurance coverage, biases in hiring and lending

that suppress earning potential of people of color and much more. Many studies suggest, though,

that racism is a fundamental cause of adverse health outcomes for racial/ethnic minorities and

racial/ethnic inequities in health. Williams provides an overview of the evidence linking the

primary domains of racism—structural racism, cultural racism and individual-level

discrimination – to mental and physical health outcomes (Williams et al., 2019). And many

studies suggest that our country’s long history of racism has influenced healthcare providers

to adopt unconscious racial biases that can affect patient care (Cooper et al., 2012;

FitzGerald & Hurst, 2017; Maina et al., 2018).

Racism is present in healthcare training.

Despite the modern understanding of race as a social

construct, basic science courses often present race in biologic terms (Tsai et al., 2016).

Racial biases that are common in the lay public are also common among medical trainees.

In one study, 50 percent of White medical students and residents held false beliefs about

biologic differences between Black and White people (Hoffman et al., 2016). There is a high

prevalence of workplace discrimination experienced by physicians of color, particularly Black

physicians and women of color, associated with adverse effects on career, work environment and

health (Filut et al., 2020). Discrimination by patients and colleagues based on skin color appears

to be common experiences of nurses as well (Wheeler et al., 2014). Students of color experience

higher levels of mistreatment by faculty than White students (Hill et al., 2020). Students who

are underrepresented in medicine are at greater risk of poor personal well-being, increased stress,

depression and anxiety (Hardeman et al., 2016). Burnout is common among resident physicians,

which can increase the expression of prejudices associated with racial disparities in healthcare

(Dyrbye et al., 2019).

How did it get this way?

While there has been spectacular progress in biomedicine, much

of the progress has come at a cost to Black and Brown people. Until the modern era, there

has been less attention to the science and art of attending to the personhood of patients and

even less to the healing potential of the relationship between patient and provider. Teaching

empathy, compassion and social justice in healthcare training is a relatively modern phenomenon.

Before the 1970s, biomedicine ruled with patients being objectified and basically serving as the

battlegrounds on which doctors and disease fought. Healthcare providers must be able to separate

themselves from the personhood and suffering of others to dissect a cadaver, to cause pain to heal

and to make objective decisions. Yet throughout the history of medicine in the U.S., this capacity

for objectification allowed physicians to be affected by prevalent stereotypes of Black and

Indigenous people and others of color, to see them as "others," to withhold empathy and to

influence their science and their patient care.

By 1619, when the first enslaved people arrived in Jamestown, Virginia, persistent negative

characterizations of Black people and people of color, in general, have justified enslavement,

violence, unconsented experimentation, forced sterilization, discrimination in housing, employment,

healthcare, incarceration and much more.

There is controversy about the origins of the idea of race. But Ibram Kendi argues persuasively

that the social construction of race began in the early 15th century with the expansion of the

African slave trade by Prince Henry the Navigator of Portugal. His biographer, Gomes Eanes de

Zurara, created blackness by lumping together the various shades of brown and the ethnic groups

that were being enslaved by his patron, Prince Henry. He described these enslaved peoples as

bestial and slothful, and believed that enslaving them and bringing them Christianity would

elevate them. The idea that blackness defined a group of people who were inferior and deserved

to be enslaved spread widely and justified the lucrative slave trade (Kendi, 2016). Beliefs in

the inferiority and other negative stereotypes of Blacks were enshrined in a steady series of

laws and social policies that have persisted until the present.

Physicians played an important role in supporting notions of the inferiority of Blacks, and

others of color, including the notion that Indigenous people were savages.

Physicians were

clearly influenced by widespread racial stereotypes and the acceptability of slavery.

(For example, 12 of the first 18 presidents were slaveholders.) Though there were many healthcare

providers who spoke out against slavery, slavery persisted for almost 250 years until its ending

during the Civil War. And the entrenched biases of many in the North and South that justified

slavery for so long persisted in Jim Crow laws (state and local laws that legalized enforced

segregation and marginalization of Black people), government policies and the suppression of

the Black vote until the Civil Rights Act in 1965. This law federally guaranteed Black

enfranchisement, but that right has been whittled away ever since. Lynching throughout the South,

as a means of terrorizing and keeping Black communities from advocating for their rights as

citizens, persisted until the 1950s.

Only in 2022 has a federal law been passed that labels lynching as a hate crime.

And modern-day lynching (public killing of an individual who has not

received due process), still occurs. Physicians are members of communities and are influenced

by the dominant culture. They have not, until recently, been at the forefront of protest and

change of structural racism.

In the 19th century, prominent physicians such as Samuel Morton, Louis Agassiz and Samuel

Cartwright "proved" through their (pseudo) scientific studies that Blacks were animalistic,

unintelligent, strong and designed for subtropical servitude. Morton, a prominent Philadelphia

physician, through his studies of skulls in the early 19th century, claimed that each of five

races had separate origins and that a descending order of intelligence could be discerned by

different skull sizes that placed Whites at the pinnacle and Blacks at the lowest. His work was

critical in "scientific racism," furthered by Agassiz, a professor at Harvard, who promoted

creationism, argued against Darwin’s ideas and supported human polygenism, that Whites and

people of color descended from different ancestors, fundamental to racist theories of the

inferiority of Black people and others of color. Cartwright, a prominent physician and medical

writer in antebellum New Orleans is remembered for his theories of "drapetomania," the disease

that causes enslaved people to run away; "rascality," the disease that made enslaved people

commit petty offenses; and "dysaesthesia ethiopica," which made enslaved people indifferent

and insensible to punishment. These and other writings that taught the inferiority of Black

people were enshrined in medical textbooks that guided young healthcare trainees

(Byrd & Clayton, 2001).

J. Marion Sims, President of the American Medical Association (AMA) in 1876, and

considered the father of modern gynecology, honed his innovative surgery by operating on

enslaved Black women without their consent and without anesthesia. Scientific racism made

possible the rise of eugenics, the notion that selected breeding could improve the human race,

which led to forced sterilization to maintain the purity and dominance of Whites by limiting

reproduction of people with undesirable traits, often people of color. Nazi Germany adopted

eugenics with the extermination of Jews and many others. Eugenics was supported by many U.S.

physicians. During the time of government sanctioned and supported forced sterilization from 1907

to 1981, up to 150,000 people were sterilized by physicians. The Tuskegee study, in which Black

sharecroppers were recruited in 1932 for a study of the natural history of syphilis and were never

treated despite the wide availability of penicillin by 1947, was shut down in 1972, but did

irreparable damage to Black people’s trust in the medical profession. The AMA has a long history

of racist practices that kept Black physicians out of medicine’s mainstream, for example, by

excluding them from membership in the AMA. This created barriers to specialty training and

professional development for Black physicians, directly harming minoritized communities who

suffered from a dearth of access to qualified physicians. For example, in 1931, there were 25,000

subspecialty trained physicians in the U.S., and only two of them were Black. This is a history

that the AMA now acknowledges and is working to build an antiracist future (Association, 2021).

Much of America's foundational wealth was built on the labor of enslaved people and the genocide and appropriation

of the lands of Indigenous people. These actions were based on declaring that these people were "savages" and in other

ways inferior to White settlers and pioneers who were creating a new country. We must acknowledge that U.S. physicians

contributed to justifying racial attitudes and practices.

In this modern era of racial reckoning, we recognize that we are moral agents in healthcare. We not only have responsibilities to put our

patients first and to treat all individuals as equals, but to work for social justice. We have a responsibility to become aware of and change

our biases and behaviors to reflect the highest ideals of our professions. We have a responsibility to contribute to changing our institutions

and laws to realize the potential and benefits of diversity, equity and inclusion. Healthcare education has recently focused on trauma informed

care. So many of our patients have experienced adverse childhood experiences and other traumas that profoundly affect their health (Bellis et al., 2019).

If we can elicit and understand the biologic and psychologic effects of that trauma, we can fashion effective therapeutic approaches to care. Similarly,

our communities of color have undergone collective and individual traumas from structural and interpersonal racism. Recognizing and appreciating this

trauma allows us to be responsible participants in the healing of our individual patients and of the society in which we all live.

Prince Akpokiro, BSc

Dennis H. Novack, MD

Structural, cultural and individual racism enacts a severe toll on the health of Black, Indigenous and people of color (BIPOC) communities. This toll includes increased morbidity and mortality when compared to White communities due to many factors, including wide disparities in wealth, the ability to afford and access care, and inadequate healthcare delivery. We discuss the many causes of these disparities from government and private policies and the adverse psychophysiological effects of the stress of racism.

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted racial health disparities. Black, Indigenous and Latinx Americans are more than twice as likely to be hospitalized and die from COVID than White Americans (Prevention, 2022). In a systematic review and meta-analysis of 293 studies, Paradies and colleagues (2015) determined that racism was associated with poorer general health, physical health and mental health. For many years, life expectancy for the Black population has been lower than for the White population, but by the height of the pandemic, the difference had increased to six years (Arias et al., 2021).

The authors go on to identify the many pathways that lead to poor health in minoritized communities: Wide earning and wealth gaps limit abilities to afford quality medical and dental care. In 2016, for every dollar of income that White households received, Hispanics earned 73 cents and Black people earned 61 cents. And racial differences in wealth are stunningly larger. For every dollar of wealth that White households have, Hispanics have seven pennies, and Black people have six pennies. Racial residential segregation, brought about by government and private policies such as redlining, mortgage discrimination, restrictive covenants and discriminatory zoning, concentrates poverty, limits job opportunities, delivers low quality education, lowers access to medical care, reduces access to healthy food choices and more. Many studies of unconscious bias show that BIPOC patients receive fewer procedures and poorer quality medical care than Whites (Williams, Lawrence, & Davis, 2019). Yearby and colleagues (2022) provide a detailed historical context and an account of modern structural racism in healthcare policy, highlighting its role in healthcare coverage, financing and quality.

There are many psychophysiological pathways that contribute to negative health outcomes of Black, Brown, Indigenous and other historically marginalized people. The lived experiences of BIPOC people who live and work in predominately White environments can be stressful. There is chronic stress related to frequent experiences of discrimination, microaggressions, microinvalidations and simply feelings of needing to constantly prove oneself as worthy in White dominant work and educational environments. This stress is associated with preclinical indicators of disease, including inflammation, shorter telomere length (indicating increased cellular aging), coronary artery calcification, dysregulation in cortisol and greater oxidative stress (Lewis et al., 2015). Self-reported discrimination has been linked to adverse cardiovascular outcomes, body mass index (BMI) and incidence of obesity, hypertension, engagement in high-risk behaviors, alcohol use and misuse, poor sleep, depression and maladaptive health behaviors, such as delaying care and reduced adherence to medical regimens (Thames et al., 2019; Williams, Lawrence, Davis, et al., 2019).

Systemic racism frequently results in persons of color and members of other oppressed ethnic groups not receiving the mental healthcare they require (Paradies et al., 2015). A survey of Black people who had not obtained formal care for a mental health issue found that respondents cited mistrust in mental health support systems because of racist experiences, stigmatization and that previous clinicians had downplayed their mental health concerns (Alang, 2019).

Using peer and community support, developing a strong sense of racial identity and talking about racist experiences can all be useful strategies of coping with racism's stress. Similarly, low socioeconomic status has negative health consequences that affect physical health and mental health (Stringhini et al., 2017). With the wealth gap and economic racial disparities among BIPOC populations, the cumulative impact of socioeconomic status further exacerbates these issues, with BIPOC people more likely to have mental health issues that last longer.

The stigmatization of mental health concerns can increase the impact of racism on Black and other oppressed communities' access to healthcare. Shame and stigma concerning poor mental health are ubiquitous in many communities, which often prevents those affected from seeking psychological help. The consequences of stigma are worse for racial and/or ethnic minorities, since they combine with other social adversities such as poverty and discrimination within policies and institutions (Eylem et al., 2020). All providers must be aware and practice with the knowledge of the intersecting factors that affect the health of their patients and those that plague communities of color that are rooted in racism and racist structures.

What is it about our psychology and our society that encourages the thriving of

racism, as well as all biases? So many biases are prevalent: homo- and transphobia,

anti-Muslim, anti-Asian, anti-immigrant sentiments, all "isms": sexism, ageism,

ableism and more. There are related questions: how did the people who founded the

United States justify, normalize and promote the enslavement of human beings?

How did they rationalize taking the lands of Indigenous people and participating

in their genocide? Since our country's founding there has been systematic

oppression and the creation of vast inequities between White people and people

of color. Are there particular processes common to the way humans think, feel

and organize their societies that allow and even encourage racism?

A biopsychosocial approach is the most effective way to understand and treat

patients' illnesses. Similarly, this approach can shed light on the questions

above. Racism is multidetermined and has complex origins, but we can summarize

a few key features of its origins in biology, psychology and the way we construct

our societies.

Though our reptilian, mammalian and then primate ancestors had been evolving for

about 320 million years, Homo sapiens emerged in Kenya and Ethiopia only 170,000

years ago. Their skins were certainly black, and all humans who are alive today

are descended from those people. We all have black ancestors. Some of our ancestors

migrated north, and over many years their skins became lighter to better

manufacture vitamin D. Fortuitous mutations in the genes that controlled facial

and tongue muscles emerged and facilitated the development of language.

Other mutations that promoted increased brain growth emerged about 40,000

and then again about 6,000 years ago. Transmission of knowledge, culture,

wisdom, the development of social structures and civilizations proceeded from

these advances. But certain survival reflexes and instincts that evolved prior

and subsequent to our emergence as Homo sapiens are still with us (Vaillant, 2008).

For all the years that we were hunter gatherers, our ancestors developed emotional

capacities that define us today. To survive in family groups and tribes, our

ancestors developed positive emotions of empathy, compassion, altruism,

love, hope, joy and faith. These emotions were critical to the success and

cohesion of family units and tribes, as well as the advancement of civilizations.

In harsh times of scarcity, though, fear gave rise to negative emotional states.

Selfishness, greed and dominance of others, competitiveness, fear of predators and

others who could harm us or encroach on resources, anger, the capacity to "otherize"

those who threatened us, and the use of violence were also survival strategies.

Seeing enemies as "others" allows us to close off empathy for their suffering.

Human history has been marked by a continual series of wars fueled by these

negative emotional states. Fear and other negative emotions are foundational in

the development of racism and other "isms." And protecting the integrity of one’s

tribe persists today.

A full discussion of the human psychology that might support racism is beyond the

scope of this section. There are some dynamics, though, that warrant special

attention.

Human children develop into adults within long periods of dependency. On the way

to achieving basic needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness (Ryan & Deci,

2000), we go through developmental stages (Erikson, 1993; Kegan, 1982), each of which

promote or undermine our sense of trust and safety in the world, and our emerging

sense of competence, independence and self-esteem. Poverty, food and job insecurity,

and social and emotional stressors can disrupt parental effectiveness and optimal

development and promote the use of psychological defenses that support prejudice.

Also, in childhood, the need for love, safety and protection from helplessness and

vulnerability results in needs for affection, admiration for strong parental figures,

and a need to gain power through words and fantasy. The need to be powerful, which

we gain in relation to others, is a core dynamic in development and a core dynamic

in hierarchical societies, such as our own. Attraction to strong authority figures

is especially keen in times of societal instability, partially explaining the rise

of authoritarian leaders, some of whom play off our fears of "the others" who commit

crimes, take our jobs, or challenge our moral and religious views of right and wrong.

Innate needs for autonomy, competence and relatedness can best be realized within

stable societies. Many who benefit from the current structure have an investment

in the stability of their societies, whether or not they are just.

To deal with anxiety and fear, humans have developed a hierarchy of psychological

defenses, some of the most immature of which are projection and denial. (Mature

defenses include sublimation, humor, altruism, anticipation, suppression and

self-assertion (APA, 1994; Vaillant, 1977). Projection and denial protect our firmly

held beliefs from being altered by facts and blame others for our troubles. Denial

helps us, for example, ignore the reality of the findings of the human genome project

that there are no biologic differences between races. Race is a social construct.

We are one race – the human race. However, centuries of pseudoscience classifying

people by race, which justified the enslavement and oppression of people of color,

persist in our sensibilities today. Collective denial and projection can assure us

that our beliefs and prejudices are "true." Other psychological defenses include

isolation of affect, devaluing others and intellectualization, all of which can

contribute to racist thinking and behaviors.

Kegan's (1982) work on adult moral development is relevant. He posits five stages

of moral development and asserts that about 65 percent of the general population

never make it past Stage 3, in which our moral reasoning relates to perceived

cultural norms. If we are in Kegan’s Stage 3, we lack an independent sense of self,

because so much of what we think, believe and feel is dependent on how we think

others experience us. It is easy to see that if we grow up in a culture that benefits

from structural racism, we accept it because it is a cultural norm. We can be

mostly unbothered by the exploitation and oppression that makes our lives possible.

If we are middle class Whites, we seek to live in White dominated communities that

offer the best schools for our children. The fact that Black and other minoritized

children receive under-resourced and inferior education is regrettable but does not

move most of us to action. We benefit from cheap clothing made by forced labor of

Uighur people in China or from the palm oil in cookies made from palm kernels

picked by child laborers in Indonesia. If we are comfortable in our lives, other

concerns – our relationships and social lives, our children’s educational

achievements and sports activities, etc. – fill our worlds.

Another human capacity is relevant in support of racist ideas – our tendency to

stereotype. With so many facts and sensations coming at us all at once, our brains

cope by making snap judgments and by stereotyping. We are constantly judging and

assessing others so that they fit into our preconceived notions and world views.

Daniel Kahneman (2011) explains how we so often make cognitive errors in judgement,

and how we can be blind to the obvious and also blind to our blindness.

There is no reality except the reality that we construct with others and agree on.

We all have points of view that are limited by the scope of our vision, our family

and cultural values, our shared history, and what we learn in school and

in the media. Many of us learned that Columbus was a hero but didn’t learn that

he was an enslaver. Some of the men who died valiantly at the Alamo, Davy Crockett

and Jim Bowie among them, were also enslavers and were fighting so that Texans could

be free to enslave Black people. They were engaging Mexico’s President General

Santa Anna’s forces who were fighting for their land and who opposed slavery.

It is often said that history is written by the victors. Our heroic version of

our American history tends to neglect that our founders who crafted the legal

bases of our country were also protecting the wealth of rich landowning White men.

"All men are created equal" did not include women, Black people or Native Americans.

Hundreds of laws, court decisions, private actions and economic and political forces

reinforced the creation of structural racism over the last 400 years of our history

in North America.

It is not human nature to be racist. We have to be taught. However, we live

in a socially constructed reality that is supported by the dynamics of human

psychology, cognition and development. They are components of our shared human

nature that we can rise above. We create our lives within a society that supports

vast disparities in wealth and opportunities. Even among those who have become

aware and troubled about inequities, many do little to change the current order

or to speak up when they observe insensitive racial slights of others. As

healthcare providers, though, we can work to understand human nature better

than others. We can strive to advance our own moral development. And we can

use our knowledge and skills to advocate for just and equitable healthcare

for all.

R. Ellen Pearlman, MD, FACH

Critical Race Theory (CRT) was developed in the late 1980s by a group of legal

scholars. This group included Derrick Bell, Neil Gotanda and Kimberlé Crenshaw.

The core idea is that race is a social construct and that racism is not merely the

product of individual bias or prejudice but has become structural. Over hundreds

of years government policies and legal decisions reflected cultural attitudes about

minoritized groups to disadvantage them in housing, employment, education,

healthcare, the justice system, etc. There are other tenets of Critical Race

Theory, such as interest convergence, which stipulates that Black people achieve

civil rights victories only when White and Black interests converge.

Furthermore, racism in the United States is normal, not aberrational: it is the

ordinary experience of most people of color. Other tenets include "intersectionality"

recognizing that one’s racial identity is only one of many ways people may identify

themselves – and that multiple marginalized identities can be especially hurtful and

confusing to identity formation; that marginalized people are in a unique position

to tell stories about their lived experiences; and that people of color are

characterized at various times with different racial stereotypes, based on the

needs of the dominant White culture.

While a review of the history of race in this country would substantiate the

truth of these observations, many conservative politicians have demonized the

teaching of critical race theory. Yet this teaching is essential for healthcare

students, who are learning their professions in an unequal and unjust healthcare

settings, and who need to advocate for change. Tsai, Wesp and their colleagues

describe how CRT education can transform medical and nursing education (Tsai et

al., 2021; Wesp et al., 2018).

Let us further consider how these concepts apply to health systems. First,

U.S. health systems were developed from the ground up within racist frameworks.

The very fabric of how we deliver care and how we educate physicians is embedded

in structural racism. It is no wonder, then, that there are significant health

disparities in all aspects of healthcare.

The following video encapsulates the idea that race is a social construct:

• The Myth of Race Debunked in 3 minutes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VnfKgffCZ7U

Delgado, R., & Stefancic, J. (2017). Critical race theory: An introduction (Vol. 20). NYU press.

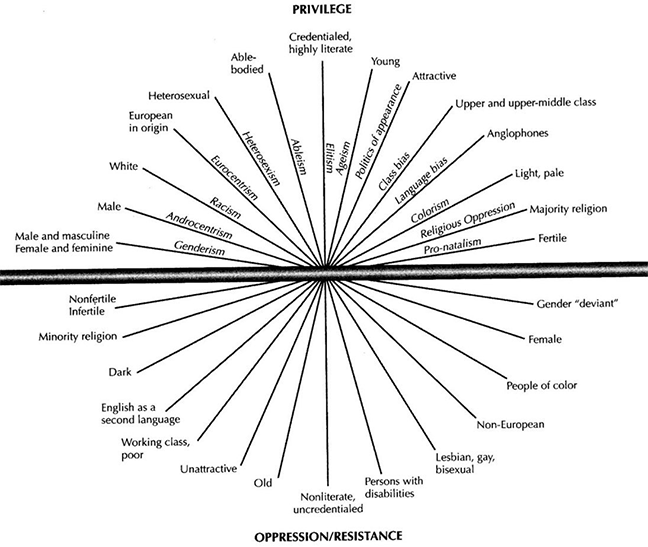

This concept was coined by legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw to explore the ways in which people with multiple marginalized identities experienced discrimination. The concept of intersectionality describes the ways in which systems of inequality based on gender, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity, disability, class and other forms of discrimination "intersect" to create unique dynamics and effects. It is important to note here that intersectionality is not the "layering on" of identities; nor is it about any/all aspects of identity. Intersectionality focuses on identities that are marginalized and argues that the point of intersection between these marginalized identities results in an erasure of the individual that ultimately results in the person’s inability to find resolution to their experiences with discrimination. Bowleg (2012) points out that individual-level experiences of people at multiple marginalized intersections typically reflect social-structural systems of power, privilege and inequality.

Kimberlé Crenshaw's "Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex:

A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory

and Antiracist Politics"

The Combahee River Collective Statement (1977)

This section addresses words we hear in popular media as "political terms" in

the culture wars. However, these words are actually rigorous theoretical frames

that directly address issues of culture, identity, privilege and power.

Colonialism is the process by which a government/nation occupies another nation

and claims that nation, its land, its people, its resources and its existence

for the benefit of the colonizing nation. Most often, these moves were justified

by referring to "the White man’s burden." This phrase referred to the responsibility

of "those made in the image of God" to bring civilization and salvation to savage and

uncultured corners of the earth. This allowed colonizers to treat the people of

colonized lands as "animalistic," "savage," uncivilized, uneducated, etc. While

colonialism has existed since ancient times, modern western colonialism began in

the mid-15th century when Prince Henry the Navigator of Portugal set up African

trading posts and initiated the African slave trade.

The impacts of colonization are immense and pervasive. Various effects, both

immediate and protracted, include the spread of virulent diseases, unequal

social relations, detribalization, exploitation, enslavement, medical advances,

the creation of new institutions, abolitionism, improved infrastructure and

technological progress. Colonial practices also spur the spread of colonist

languages, literature and cultural institutions, while endangering or

obliterating those of native peoples (Wikipedia).

While presumed that the era of colonialism has ended, colonialism is still

prevalent in current global politics and its impacts continue to reverberate

throughout the world. Colonialism goes beyond "the takeover" of a country. It

includes infiltrating the colonized country with the language, culture and values

of the colonizing nation. For example, the British imported their train system to

India. This was not simply the development of railroad systems for India. It also

carried with it the values of "time and efficiency," marking them as important

characteristics for a "successful" society. We see this in contemporary presumptions

such as "progress" and "life-saving techniques." Colonialism also includes the

taking of resources from the colonized peoples, which includes not only material

objects (such as gold, diamonds or copper) but also cultural knowledge and practices

and claiming them as "discoveries," negating the science and knowledge of ancient

cultures.

Colonialism set the groundwork for western science to be seen as the

"first" true science. It allowed for scientific discovery to be intertwined

with the "salvation" of uncivilized peoples. This then allowed western science

to describe non-western bodies and practices as inferior, as well as demonic,

deviant, diseased, and pathological. These attitudes infiltrated the development

of health systems and the care of marginalized people for centuries and persist

today.

• Albert Memmi's "The Colonizer and the Colonized"

• Franz Fanon's "Wretched of the Earth" and "Black Skin, White Masks"

Racism is overwhelmingly thought to be "bad acts and beliefs by bad people."

This frames it as an interpersonal, immoral, individual act. As the previous

sections of this module explain, racism, like race, is a socially constructed

phenomena and functions at society’s structural level. Individual, institutional

and social acts of racism manifest through sustained structures that create and

reinforce racism.

Structural racism in the U.S. can be defined as the normalization and

legitimization of an array of dynamics – historical, cultural, institutional

and interpersonal – that routinely advantage Whites while producing cumulative

and chronic adverse outcomes for people of color. It is a system of hierarchy and

inequity, primarily characterized by White supremacy.

Structural racism encompasses the entire system of White supremacy, diffused and

infused in all aspects of society, including our history, culture, politics,

economics and our entire social fabric. Structural racism is the most profound

and pervasive form of racism – all other forms of racism (e.g., institutional,

interpersonal, internalized, etc.) emerge from structural racism. Structural

racism has shaped the delivery of care and the science of medicine. For example,

many clinical algorithms used today are based on faulty or pseudoscientific

observations of racial differences. Nyas and colleagues (2020) argue that we

need to reconsider use of race corrections to ensure that our clinical practices

do not perpetuate the very inequities we aim to repair.

Gloria Yamato's essay "Something about it is hard to name", In Margaret L. Anderson and Patricia Hill Collins. eds. 2004. Race, Class, and Gender. 5th Ed. NY: Thomson/Wadsworth Pub. Pp. 99-103. (https://likeawhisper.files.wordpress.com/2010/03/somethingaboutthesubject.pdf)

Foundational concepts, principles, and duties guiding contemporary clinical ethics provide a clear mandate for antiracist action in the care of patients and communities. Key points for understanding include social contract, human rights, guiding ethical principles, essentials of caring, and virtue as personal commitment.

As members of healthcare professions, we are entrusted with

the lives and wellbeing of our patients. Each profession

enters into a binding contract with society. Society entrusts

clinicians with powers and privileges to care for patients.

As examples, society allows each profession sets its own

standards and training. Clinicians are permitted access to

patients’ bodies and personal information. We make treatment

decisions that have consequences for patients’ lives. We are

permitted unsupervised interaction with people during their

most vulnerable times. As a student or practitioner, you enjoy

these permissions and freedoms only because you are a member

of your healthcare profession.

In exchange, all members of every healthcare profession are

bound to a responsibility to serve the best interests of

patients and society. Clinicians are guided in this by ethical

principles and ethical commitments that have changed

dramatically over time and continue to evolve. The

emergence of autonomy and social justice as guiding ethical

principles are two key examples that mark a sea-change in

ethical thinking and action of antiracism in medicine and

healthcare.

Historically and until around the 1950s-1960s, guiding

principles in medical ethics were beneficence (doing the most

good for a patient) and non-maleficence (avoiding harm to that

patient). Physicians made treatment decisions based on their

professional understanding of what was good or bad for the

patient, often in disregard of patients’ values or choices.

In the US, the period around the 1960s was one of social

change driven by movements related to civil rights, feminism

and gender equality, rights of the incarcerated, rights of

human research subjects, and consumer rights. Historically

oppressed or disempowered groups demanded recognition as fully

equal members of society and self-determination—control over

one's own life and life decisions.

At the same time, rapidly emerging technologies such as

ventilators, organ transplantation, and radical surgeries

raised critical quality of life concerns: just because a

treatment could be done, does not mean it should be, especially

because the patient may not want to live with the consequences.

In both of these contexts, social and individual, autonomy

emerged as a central guiding principle of modern bioethics.

Autonomy means having control over one’s own body, mind, and

life decisions, free from oppression and coercion. It is a

human right.

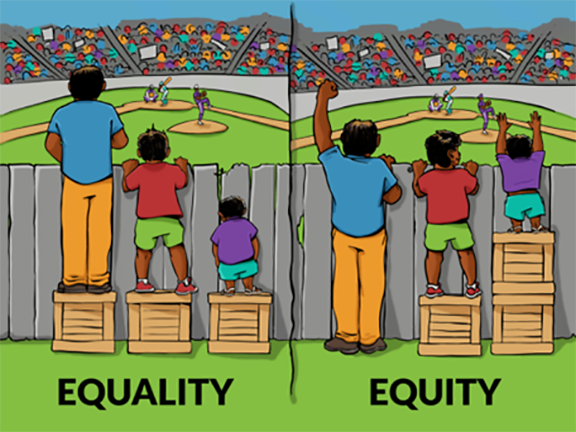

As modern bioethics emerged during the 1960s and 1970s, the principle of social justice featured as another fundamental, guiding principle. The interpretation and application of this principle has continued to develop and has gained increasing prominence and significance. Applications of the social justice principle have always included the equitable distribution of limited healthcare resources (distributive justice). Social justice also always informed the negotiation between individual autonomy and health of the public: individual autonomy must be curtailed at times in the service of public health (e.g., quarantine, mandated vaccinations, mandatory reporting of certain diseases and conditions). Belatedly, mainstream clinical ethics has now intensified and broadened its understanding of social justice to also address structures of racism and other social oppression and practitioner bias as they relate to patient care and outcomes and the health of communities.

Quality clinical care and ethical care are inseparable.

It happens too often that an indicated treatment is provided,

but in a way that undermines autonomy, injures the patient

emotionally, and/or turns the patient away from seeking

necessary care in the future. This is unfortunately an

experience of BIPOC and other members of our community who

have suffered discrimination, bias, or stigmatization.

On a more macro level, a patient may be presenting with a

medical need that was caused or exacerbated by structural

barriers to the determinants of health and survival (healthcare,

food, income, education, safe housing, social integration).

A child of color may have uncontrolled asthma because of

unhealthy housing conditions resulting from generational

disenfranchisement and redlining that placed affordable,

healthy housing out of reach.

We must always see this inextricable joining of clinical and

ethical care. Clinical questions are: what is the correct

diagnosis and how do I administer the correct treatment?

Simultaneous ethical questions are: How do my words and

actions as a clinician respect patient autonomy, demonstrate

my trustworthiness, and reflect the appropriate management of

professional power to achieve the most good and avoid harm?

Clinicians view patient care through multiple ethical frames

that ultimately justify antiracist objectives. These are:

PRINCIPLES. As already introduced in this discussion,

contemporary clinical ethics employs guiding principles.

These include respect for persons, autonomy, beneficence

and non-maleficence, and social justice.

SOCIAL CONTRACT. Every patient interaction must fulfill

the promise of this contract, use professional power

and privilege only in the service of our patient.

This is a contract of trust and trustworthiness, and

all actions are to directly or indirectly promote trust.

Trust is the foundation of any patient encounter and we

do not take it for granted. We have come to increasingly

realize the complex roots of patient distrust of the

US medical system that include historic mistreatment

and abuse of black, indigenous, and other people of color.

VIRTUE. Clinicians must develop their own capacity to be guided

by ethical principles and uphold the social contract even

under challenging and difficulty circumstances. Throughout

our professional lives we deepen our capacities for

compassion, excellence, moral courage, and other moral

qualities in the service of patient care. Today we

realize this must include overcoming race and other

bias in ourselves, intervening to the extent we are

able when witnessing racism or discrimination in the

healthcare setting, and working to overcome structural

racism and other barriers to health equity.

Medical ethics have been heavily influenced by racism, specifically through the false assumption of race as a biological difference rather than a social construct. Historical trauma has an impact across generations and has resulted in a high level of mistrust of patients toward clinicians. It is the responsibility of healthcare clinicians to understand the impact of structural racism and implicit bias as they relate to their own ethical decision-making.

Ethical decision-making as a clinician requires you to understand the

professional code of ethics you are accountable to, relevant legislation,

and the influence of history and tradition on the practice of medicine.

Accountability to a code of ethics is a key element of defining any profession.

Cruess et al. (2004) in their definition of "profession," emphasize that any

profession "must be governed by codes of ethics and profess a commitment to

competence, integrity and morality, altruism, and the promotion of the public

good within their domain. These commitments form the basis of a social contract

between a profession and society, which in return grants the profession a

monopoly over the use of its knowledge base, the right to considerable autonomy

in practice and the privilege of self-regulation. Professions and their members

are accountable to those served and to society." This social contract in the

medical profession is heavily influenced by both legislation and tradition.

You can see that your ability to adhere to the four principles of ethical

decision making in healthcare can be influenced by implicit and explicit

biases within a healthcare system that has been shaped by structural racism.

These principles are: beneficence (doing good), non-maleficence (doing no harm),

autonomy (giving the patient the freedom to choose freely, where they are able)

and justice (ensuring fairness in care.)

The impact of racism on medical ethics is well-documented. Medical research

has persistently maintained assumptions that there are physiologic and genetic

differences based on race, though it is proven that race is a social construct.

When medical researchers continue to search for false correlations between race

and disease, the more important focus on public health and the roles that social

determinants of health play in health outcomes for marginalized populations is

lost (Perez-Rodriguez, & de la Fuente, 2017). Research that begins with the

assumption of race as a biological rather than social construct leads to

inherently unethical and unequal treatment decisions. To maintain an ethical

social contract between you as the clinician and your patients, you must

critically evaluate your understanding of the impact of historical trauma

and unconscious bias. Your relationship with your patients must be informed

by your understanding of these concepts, as well as the roles that social

determinants of health may play in your treatment decisions and health

outcomes for your patients.

Key Point: Medical ethics has been heavily influenced by racism,

specifically through the false assumption of race as a biological difference

rather than a social construct.

Historical Trauma

Historical trauma is defined as the cumulative effect of

harm that spans generations and can impact both physical and emotional

wellbeing (Gameon & Skewes, 2020). Historical trauma is a barrier to full

access to healthcare for people of color. The history of exploitation of

people of color in the name of medical advancement and the resulting trauma

undermines the trust between patient and provider. You are most likely familiar

with many examples of unethical and traumatic medical mistreatment of Black

people in the United States. The Tuskegee Syphilis Study, conducted by the U.S.

Public Health Service, surgical experiments on Black women and the use of

cancer cells for research without consent represent just a few of the many

traumas inflicted upon Black people.

Access to healthcare was segregated from the beginning of the medical profession

in the United States. Racial disparities in the delivery of care were intentional

early in the history of medicine, and the result was consistently poor health

outcomes for Black people and a deep mistrust of the medical profession (Miller &

Miller, 2021). Patient/client trust in your care is essential for you to be

able to deliver care on an ethical foundation. Mistrust in science and in

healthcare clinicians is endemic in the U.S., as seen in vaccine hesitancy

and reluctance to participate in clinical trials. A number of studies

illustrate how the legacy of structural racism has generated mistrust in Black

communities that contribute to stark healthcare disparities (Powell, 2019; Warren,

2019; Warren, 2020).

Historical trauma is not limited to the experiences of Black people.

Asian American Pacific Islanders have also been subjected to racism and the

resulting negative impact on health outcomes. Japanese Americans were detained

in camps after the 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor. In subsequent studies on the

intergenerational impact of internment it was found that there were disparate

health outcomes for those who were detained in the camps, loss of family businesses

and a negative impact on mental health for future generations, as well as a

mistrust of the government (Patel & Nagata, 2021). In the 20th century, about

one third of women of childbearing age in Puerto Rico were coerced into becoming

sterilized. This was promoted and subsidized by the United States government

through Puerto Rican public health institutions (Lazare, 2021). In the 1940s,

U.S. Public Health Service researchers intentionally exposed over 1,300 sex

workers, soldiers, prisoners and psychiatric patients to sexually transmitted

diseases (STDs) without their consent to test the effectiveness of prophylactic

interventions (Spector‐Bagdady, 2019).

These experiences of historical trauma represent just a small portion of the

number of unique histories that people of color in the United States bring with

them into their healthcare encounters. It is important for you to consider the

possible impact of historical trauma on trust and confidence in your ability and

willingness to care for your patients. It is critical that you take concrete steps

to demonstrate that you understand the background, history and experiences of your

patients, their communities and their cultures. There are ways to build trust so

that you can work toward a more effective patient-physician relationship.

Explicitly acknowledging the history of racism in medicine and encouraging

patients to share their stories and their biases could lay the groundwork for

a more trusting relationship. Asking patients what they need from you to build

trust can also be a pathway to intentional conversations that will deepen the

patient-physician relationship (Miller & Miller, 2021). Finally, you can

continue to research and educate yourself on the complex intersection of the

history of racism and medicine as it relates to marginalized populations so

that you understand the perspective of these patients. Taking these steps

will help you to develop your trustworthiness as a physician as you work with

your patients toward better health outcomes.

Key Point: Historical trauma has an impact across generations and has

resulted in a high level of mistrust of patients toward physicians. There are

specific, intentional steps that you can take as a physician to mitigate the

impact of historical trauma and support the ethical practice of medicine.

The COVID-19 pandemic amplified the need for ethical decision-making in

medicine and further emphasized significant disparities in care for marginalized

communities. The convergence of poor health outcomes due to existing social

determinants of health and systemic disparities in access to care resulted

in more people of color who were disproportionately in need of hospitalization

due to the virus (Tochin et al., 2020). Once these patients arrived at the

hospital, triage protocols in place to manage limited resources further

disadvantaged people of color. Traditional methods of medical decision-making

in allocating scarce resources falsely assume a baseline measure of health and

do not take into account the impact of systemic racism and social determinants

of health on diverse patient populations (Schmidt et al., 2020). This is just

one example of many that represents the complexity of ethical decision-making

in healthcare and the persistent negative impact of structural racism in the

delivery of healthcare.

In a study examining disparities in the treatment of pain for Black and White

patients, researchers examined the beliefs of medical students and residents about

biological differences between the two patient groups (Hoffman et al., 2016).

The study concluded that medical students who endorsed the belief about

biological differences made unequal treatment decisions due to falsely held

beliefs about biological differences between Black and White patients

(Hoffman et al., 2016). In another study, Perez-Rodriguez and de la Fuente

(2017) examined the interpretation of research studies on the prevalence

of a particular form of breast cancer (TNBC) among Black women. The results

of the study were reported solely based on the race of the women but failed

to account for the fact that in each category of analysis, there was strong

evidence that socioeconomic status and Medicaid as the primary insurance

coverage were also significantly related to the presence of TNBC.

A study demonstrating how implicit bias can affect medical decision making

showed videos of patients complaining of symptoms suggestive of coronary artery

disease to 720 primary care physicians. The actors varied by age, race and gender

but told the exact same stories of their symptoms. They found that women

(odds ratio, 0.60; 95 percent confidence interval, 0.4 to 0.9; P=0.02) and

blacks (odds ratio, 0.60; 95 percent confidence interval, 0.4 to 0.9; P=0.02)

were less likely to be referred for cardiac catheterization than men and Whites

(Schuman et al., 1999). The book Unequal Treatment by the Institute of Medicine

documents the many ways that racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare are

significant predictors of the quality of healthcare, even after accounting for

the effects of socioeconomic conditions (Smedley, Stith, Nelson, 2003).

These examples emphasize that your responsibility as a clinician is to constantly

engage in critical self-reflection to ensure that your treatment decisions are

based on the individual factors for each patient and that your decisions are free

from racial bias. Because implicit bias can influence your decision-making, you

can seek objective input from other peers on a routine basis to ensure that

you are aware of any blind spots or concerning patterns in your treatment

decisions. Listen to your patients carefully and identify

support people to help advocate for patients, such as social workers,

community health workers, etc. Additional responsibility of the clinician

is to effectively communicate with patients regardless of their preferred

language. This includes effective use of professional interpretation services

and knowledge of institutional policies.

Commit to

continuing education to better understand the impact of implicit bias on

medical decision-making. Finally, you can actively advocate for changes to

the medical school curriculum that continues to teach that there are biological

differences between races. Williams et al. (2018) found that when medical

schools intentionally incorporate these concepts throughout their curriculum,

their students are less likely to demonstrate biased medical decision-making

behaviors.

Key Point: Structural racism has influenced the field of medicine and

continues to inform research and medical education. It is a false belief that

there are biological differences between races. It is the responsibility of

clinicians to understand the impact of structural racism and implicit bias as

they relate to their own ethical decision-making.

To ensure that your care is based on the ethical foundations of beneficence,

non-maleficence, autonomy and justice, you have an ethical responsibility to

understand the impact of structural racism on the practice of medicine. The

resulting historical trauma experienced by multiple marginalized people negatively

impacts the development of a trusting and effective patient-clinician relationship.

Your treatment decisions are influenced by your unexamined implicit biases. You are

responsible for actively working to build trust with your patients and for being aware

of your biases and how they may be impacting your treatment decisions. As a clinician

you have the capacity to challenge long held misconceptions in the

field of medicine that uphold racist practices.

R. Ellen Pearlman, MD, FACH

According to Delgado and Stefancic (2001), race-consciousness is explicit

acknowledgment of the workings of race and racism in social contexts or in

one's personal life. In healthcare, this means acknowledging that racial health

inequities are the result of racism, not the result of genetics. Applying

race-consciousness to healthcare requires:

• an appreciation of the complex historical journey

of Black people and/or persons of color;

• knowledge of disparities in health which

may facilitate or inhibit optimal levels of care for these individuals

and their families;

• and the self-appraisal of one's attitudes, feelings,

beliefs and biases towards Black people and/or persons of color (Watts, 2003).

Race-consciousness is often juxtaposed to colorblindness, which acknowledges

the arbitrary nature of race, yet ignores the inequities created as a result of

structural racism.

When we talk about having privilege, what exactly do we mean? A privilege is an unearned, mostly unacknowledged societal advantage (right, benefit, or immunity) that a restricted group of people has over another group. The nature of privilege in systems of oppression is that those who possess it are frequently unaware of it. Peggy McIntosh, in her seminal article, describes how "privilege is like an invisible weightless knapsack of special provisions, maps, passports, codebooks, visas, clothes, tools, and blank checks." She proceeds to write down examples from her daily life of "White" privilege that she has taken for granted. The following are excerpts from her list:

- If I should need to move, I can be pretty sure of renting or purchasing housing in an area which I can afford and in which I would want to live. I can be pretty sure that my neighbors in such a location will be neutral or pleasant to me.

- I can go shopping alone most of the time, pretty well assured that I will not be followed or harassed.

- I do not have to educate my children to be aware of systemic racism for their own daily physical protection.

- I can be pretty sure that if I ask to talk to the "person in charge," I will be facing a person of my race.

- If a traffic cop pulls me over or if the IRS audits my tax return, I can be sure I haven't been singled out because of my race.

- I have been taught since an early age that people of my own race can become doctors.

- Throughout my education, I could succeed academically without people questioning whether my accomplishments were attributable to affirmative action or my own abilities.

- When I applied to medical school, I could choose from many elite institutions that were founded to train inexperienced doctors of my race by "practicing" medicine on urban and poor people of color.

- I am reminded daily that my medical knowledge is based on the discoveries made by people who looked like me without being reminded that some of the most painful discoveries were made through inhumane and nonconsensual experimentation on people of color.

- When I walk into an exam room with a person of color, patients invariably assume I am the doctor in charge, even if the person of color is my attending.

- If I respond to a call for medical assistance on an airplane, people will assume I am really a physician because of my race.

- Every American hospital I have ever entered contained portraits of department chairs and hospital presidents who are physicians of my race, reminding me of my race’s importance since the founding of these institutions.

- Even if I forget my identification badge, I can walk into the hospital and know that security guards will probably not stop me because of the color of my skin.

- I have been taught since an early age that people of my own race can become doctors.

- Throughout my education, I could succeed academically without people questioning whether my accomplishments were attributable to affirmative action or my own abilities.

- When I applied to medical school, I could choose from many elite institutions that were founded to train inexperienced doctors of my race by "practicing" medicine on urban and poor people of color.

- I am reminded daily that my medical knowledge is based on the discoveries made by people who looked like me without being reminded that some of the most painful discoveries were made through inhumane and nonconsensual experimentation on people of color.

- When I walk into an exam room with a person of color, patients invariably assume I am the doctor in charge, even if the person of color is my attending.

- If I respond to a call for medical assistance on an airplane, people will assume I am really a physician because of my race.

- Every American hospital I have ever entered contained portraits of department chairs and hospital presidents who are physicians of my race, reminding me of my race’s importance since the founding of these institutions.

- Even if I forget my identification badge, I can walk into the hospital and know that security guards will probably not stop me because of the color of my skin.

She describes White fragility as "…a state in which even a minimum amount of racial stress becomes intolerable, triggering a range of defensive moves. These moves include the outward display of emotions such as anger, fear, and guilt, and behaviors such as argumentation, silence, and leaving the stress-inducing situation. These behaviors, in turn, function to reinstate White racial equilibrium" (DiAngelo, 2011).

The following table shows the typical emotional reactions, behaviors, and claims that White people make in conversations about race that indicate fragility.

| Emotional Reactions to Receiving Feedback about Bias | Behavioral Reactions to Receiving Feedback about Bias | Common Claims Made after Receiving Feedback about Bias |

|---|---|---|

Feeling…

|

Crying Physically leaving Emotionally withdrawing Arguing Denying Focusing on intentions Seeking absolution Avoiding |

"I know people of color." "You are judging me." "You are generalizing." "You’re playing the race card." "You’re being racist against me." "You are making me feel guilty." "You hurt my feelings." "The real oppression is class (or gender, or anything other than race)." "I don’t feel safe." "The problem is your tone." "That was not my intention." "I have suffered too." |

| The 11 Unspoken Rules of White Fragility | |

|---|---|

| 1 | "Do not give me feedback on my racism under any circumstances." This is a cardinal rule. However, if you break this rule, then make sure to follow the others. |

| 2 | "Proper tone is crucial - feedback must be given calmly. If any emotion is displayed, the feedback is invalid and can be dismissed." |

| 3 | "There must be trust between us. You must trust that I am in no way racist before you can give me feedback on my racism." |

| 4 | "Our relationship must be issue-free - if there are issues between us, you cannot give me feedback on racism until these unrelated issues are resolved." |

| 5 | "Feedback must be given immediately. If you wait too long, the feedback will be discounted because it was not given sooner." |

| 6 | "You must give feedback privately, regardless of whether the incident occurred in front of other people. To give feedback in front of any others who were involved in the situation is to commit a serious social transgression. If you cannot protect me from embarrassment, the feedback is invalid, and you are the transgressor." |

| 7 | "You must be as indirect as possible. Directness is insensitive and will invalidate the feedback and require repair." |

| 8 | "As a White person, I must feel completely safe during any discussion of race. Suggesting that I have racist assumptions or patterns will cause me to feel unsafe, so you will need to rebuild my trust by never giving me feedback again. Point of clarification: when I say "safe," what I really mean is "comfortable."" |

| 9 | "Highlighting my racial privilege invalidates the form of oppression that I experience (e.g. classism, sexism, heterosexism, ageism, ableism, transphobia.) We will then need to turn our attention to how you oppressed me." |

| 10 | "You must acknowledge my intentions (always good) and agree that my good intentions cancel out the impact of my behavior." |

| 11 | "To suggest my behavior had a racist impact is to have misunderstood me. You will need to allow me to explain myself until you can acknowledge that it was your misunderstanding." |

According to DiAngelo, White fragility serves the following functions; It:

- Maintains White solidarity,

- Closes off self-reflection,

- Trivializes the reality of racism,

- Silences the discussion,

- Makes White people the victims,

- Hijacks the conversation,

- Protects a limited worldview,

- Takes race off the table,

- Protects White privilege,

- Focuses on the messenger, not the message, and

- Rallies more resources to White people.

DiAngelo argues that in order to dismantle structural racism, White people will need to learn to tolerate discussions around race and racism without becoming defensive or apathetic. She suggests that White people learn to approach conversations about race with a growth mindset by consciously working to shift emotions, behaviors, and responses to engage in the conversation. See the table below for her suggestions:

| Reframe Your Emotions to Receiving Feedback | Behavioral Reactions to Receiving Feedback | Reframed Claims to Make in Response to Feedback |

|---|---|---|

Embrace…

|

Engage in…

|

State…

|

- Seeing White Fragility: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CdFCRHhygHo

Robin DiAngelo comments on her work in these videos:

The nature of racial conflict is introduced and contributing factors are discussed, especially in the context of healthcare. Racial conflict is inextricably linked to stereotypes, bias, privilege, discrimination, racism and inequities.

Racial conflict is a type of social conflict that results in threatened or actual

harm to the targeted racial group based on perceived racial differences. Outright

racism, oppression, discrimination, mistreatment, and offensive racist words and

actions underlie racial conflict. After learning key concepts of race, racism and

the history of racism in the U.S., it may be easier to grasp why racial conflict

exists. The stereotypical perception and treatment of an entire racial group as

"less than" inevitably results in grievances and eventually generates conflict

as disadvantaged groups challenge the status quo and compete for power and resources.

The additional context of the history of racism in healthcare (Hess et al., 2020),

specifically, reveals the grim reality of systemic racial inequities leading to

health and social disparities (Ricks et al., 2021; Sim et al., 2021). In the U.S.

today, we see how minoritized racial groups continue to suffer restricted access to

basic needs such as healthy foods, clean air and water, safe areas for exercise and

access to healthcare (Johnson-Agbakwu, 2022). These same marginalized populations

already face disparate health outcomes (Sim et al., 2021) and continue to be

subjected to race-based chronic stress due to generations of exposure to

discrimination and injustice.

Healthcare can be added to the list of resources for which minoritized racial

groups must compete. Certainly, White privilege and fragility play a large role

in maintaining a system that serves to sustain these inequities and serves to keep

White people from fully grasping the depth and breadth of the problem (Hess et al.,

2020). How can White people mitigate racial conflict? What are the processes and

pathways for moving away from inequity and toward empathy, understanding and

transformative change in healthcare (Hagiwara et al., 2019; Hess et al., 2020;

Sim et al., 2021) for Black people and people of color? It is imperative to reckon

with the historical racial discrimination and mistreatment, and to acknowledge

the disparities that lead to shortening people’s life span by 20 years, simply as

a function of their zip code. Trainees and healthcare professionals entering the

field must shine a light on the role of racial conflict in ongoing health inequities,

refuse to contribute to and/or sustain the distortions of racial bias and lead the

transformation to equitable healthcare.

Bias is defined and presented as the root of racism and unequal healthcare treatment. Neuropsychology explains how stereotypes and bias develop, and research has identified possible ways to measure and mitigate bias.

Biases are learned beliefs and attitudes about others that may be positive or

negative, like prejudice and stereotypes. Biases are formed early in life through

exposure to biased media, education and people, and they are often culturally

reinforced. Racialized medical theories from the 1850s that people of African

descent have a higher threshold of pain, still contribute to bias today and affect

medical practice. Studies show evaluation and treatment of pain for Black patients

compared to Whites was negatively impacted by medical students who endorsed this

racial bias. Racial bias is also closely linked to health inequities. Bias ranges

from subtle microaggressions to more overt episodes of major bias, and both can be

detrimental to health and well-being. Being targeted on a daily basis naturally

leads to heightened watchfulness or even vigilance, which has serious implications

for chronic stress and health. An APA article (2022) highlights vast disparities in

access to healthcare that were exposed by the COVID-19 pandemic. One serious outcome

is how people of color were hit harder by COVID-19 due to institutionalized racism.

Psychologists assert that racism is the root cause of unequal healthcare treatment,

policies and access in the U.S.

Black people and other non-White racial groups regularly face discrimination from

healthcare providers. Providers may be aware or conscious of some bias and unaware

of other aspects of bias (e.g., implicit bias). The human brain makes rapid and

automatic associations, naturally putting things in categories to make sense of

the world. Stereotyping is an automatic cognitive process of generalizing and

placing people in categories, which is more likely to occur under conditions of

stress. A stereotype is a generalization about a person or group of people without

regard to individual differences. Even stereotypes that seem positive may have

negative consequences.

Negative bias leading to mistreatment often stems from fear and misunderstanding of

difference. Whether implicit bias, prejudice or stereotypes, these attitudes affect

our understanding, actions and decisions. Since conscious and unconscious bias

involve learned stereotypes, values and behaviors, it is believed that they can

be unlearned and reduced through conscious attention. If you are a member of a

minoritized group, negative stereotypes can undermine your self-esteem. One popular

strategy for mitigating bias is to learn more about your own unconscious bias by

taking the Harvard Implicit Association Test

(IAT https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/),

raising self-awareness and applying

various strategies to become more conscious of how your biases may affect your

behavior, decisions, and self-esteem. By slowing things down, people are likely to

align their conscious beliefs, values and behaviors in more equitable treatment of

others.

To cultivate a more diverse workforce in healthcare and positively affect patient

outcomes and health equity, we must find ways to effectively intervene with our own

bias and associated behaviors. Sometimes a biased response may be avoided by naming

it, reflecting and replacing it with a more reasoned choice. Creating

counter-stereotypic images can help to challenge the validity of a stereotype.

Exposure to those who are different from oneself often provides specific information

about group members that can prevent stereotyping in the future. It also helps trying

on the perspective of others. Extensive research and discussion of these and other

interventions are discussed in Science of Equality article (2014) about addressing

implicit bias. Studies, such as Burke et al. (2017), are developing and testing new

strategies for addressing implicit bias, stereotypes and prejudices

held by providers.

Cultivating your emotional intelligence is essential to understanding the

experiences of racially minoritized individuals and countering your implicit